Continuing the story from last month, the Knoxville-based Great Smoky Mountains Conservation Association hired Paul Adams to build a proper campsite on Mount Le Conte, just over 100 years ago, in the summer of 1925. As a young, experienced outdoorsman, naturalist and trail guide, Adams eagerly embraced the task with his intelligent canine companion, Smoky Jack, who was now equipped with leather saddlebags to help pack supplies up and down the mountain.

Adams first introduced Jack to Charlie Ogle, the owner of a general store in Gatlinburg. Since the dog weighed 90 pounds, Adams felt that the German Shepherd shouldn’t carry more than a third of his body weight. Fifteen pounds of supplies in each pocket would be enough. Protective of his assignment, the dog would never let anyone pet him when carrying a load.

When Adams wanted to send the loyal dog down to get more supplies, he would issue the command: “Go to the store, Jack. Store!” And off the dog would trot, five miles or more down to Gatlinburg. On arrival, he would bark and then allow Mr. Ogle to fill his saddlebags before making the return journey on his own.

One day, Jack arrived at the store and found that Ogle had gone to Knoxville, so he waited several hours for him to return. Making several round trips per week, Jack soon earned his keep. His treks not only saved Adams time away from camp, but they also saved portage fees for the Conservation Association, incurred every time the store delivered small supplies up the trail.

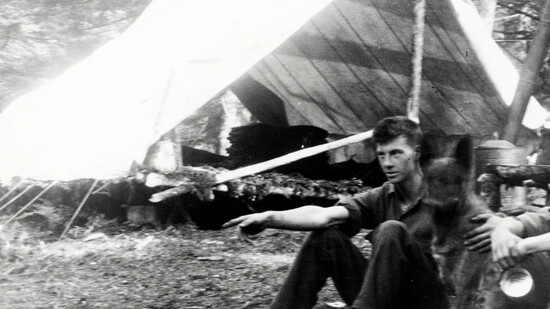

In late July 1925, Adams cleared a gap in the woods on top of Le Conte and erected a large tent to accommodate the first group of visitors to camp. He would have been well acquainted with most of the overnight hikers in this party, which included the Ijams family and members of the recently formed Smoky Mountain Hiking Club, including Knoxvillians Brockway Crouch, Albert “Dutch” Roth, and well-known photography brothers Jim and Robin Thompson. Jim arranged the picture, but Robin took the shot with a wide-angle lens. It’s a genuine classic of the early national park era. Adams can be seen holding an axe while Smoky Jack is hiding under the table—although he was well-behaved, he could also be stubborn, refusing to come out of the shadows for a glamor shot!

Another day that summer, Adams walked down to Gatlinburg to get some supplies of his own. Jack came along, but as they were coming down the Rainbow Falls Trail, the dog, shortly ahead of his master, halted suddenly and began to loudly bark and growl. Adams thought the dog had possibly seen a snake, but as they carried on, an armed man wearing a fake mustache and a

wig appeared from behind a tree and told Adams to put his hands up.

The man took away Adams’ pistol from his belt, emptied the bullets and demanded money. He told Adams that if he should turn around before he had the chance to escape, he would shoot. Adams wasn’t about to argue, and within a few moments the highwayman was gone.

Adams encountered the bandit several more times until he realized that the assailant had figured out when large numbers of campers had paid their fees, and Adams likely had a sizable wad of cash on him. From then on, he placed most of his camp money safely in Smoky Jack’s saddlebags. He knew that the dog would be a reliable security guard if needed.

Another escapade included memorable interactions with a timber wolf (or eastern wolf), which was then thought to have been locally extinct for more than 20 years. One afternoon, Adams saw Smoky Jack come racing into camp, followed by something unseen. As he wrote in his journal, he cocked his gun and “a lone timber wolf came bursting out of the tangle of blooming hobblebush, ferns and bush-honeysuckle, intent on catching Jack.” The wolf came a few yards into camp, but Jack’s snapping barks were enough to scare the wolf, which wheeled sharply around and took off back into the woods. Over the coming months, they would see the wolf a few times more. The very last time the pair encountered the wolf in the Smokies would be in 1929.

Adams continued to manage the Le Conte camp until the spring of 1926, when he moved to Alpine, Tennessee, where his father served as a pastor. Jack Huff (son of Andy Huff, owner of the Mountain View Inn in Gatlinburg), took over the job and further improved the camp, building what would become the first proper version of what we know today as the famous LeConte Lodge. Still, the stories of Paul Adams and Smoky Jack continue to enthrall readers interested in the legends of Great Smoky Mountains National Park. Today, carefully preserved in the park’s archive in Townsend, the most requested item to be viewed by visitors is the saddlebags worn by Jack all those years ago.

Recommended Reading: Smoky Jack and Mount Le Conte (UT Press, 2016), featuring new introductions and extensive footnotes by Smokies experts Anne Bridges and Ken Wise, is based on Paul Adams’ memoirs; and LeConte Lodge: A Centennial History of a Smoky Mountain Landmark by Tom Layton and Mike Hembree (McFarland Publishers, 2025).

About KHP: The educational nonprofit Knoxville History Project tells the city’s true stories, focusing on those that have not been previously told and those that connect the city to the world. Donations to support the work of KHP are always welcomed and appreciated. Learn more at KnoxvilleHistoryProject.org.