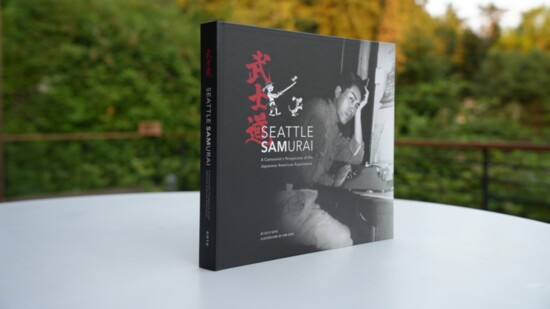

This fall, Seattle Samurai, a unique blend of Japanese heritage and cartoons, was released at Island Books. The collection, created by the late Mercer Islander Shigeru “Sam” Goto, was compiled by his daughter, Kelly. Sam, inspired by comics like Lil Abner and Peanuts, used his art to blend humor and Japanese culture. Kelly organized his work around key aspects of Japanese tradition, making Seattle Samurai both entertaining and culturally rich.

Sam, influenced by the mastery of Charles Schulz, infused his work with humor and wisdom, creating a unique connection between Japanese-American values and comic art. His beloved strip Tomadachi not only entertained but became an important archive of the Japanese-American experience. Kelly’s thoughtful layout, featuring sepia-toned photos and well-spaced text, enhances accessibility for all readers.

The character “Inu” the dog brings humor to the comic strips, adding a light-hearted, relatable touch for readers of all ages. This charming element of Sam’s work helped make Tomadachi a cultural touchstone for the Japanese-American community in Seattle.

After Sam’s passing, Dee Goto, his wife, embraced lifelong learning. Fascinated by podcasts, Dee immersed herself in this new medium, continuing to grow personally and share her passion for learning. Her dedication to learning reflects the legacy she and Sam built together.

Dee was instrumental in bringing Sam’s talent to a broader audience. Recognizing that the North American Post, a key publication for Seattle’s Japanese community, needed fresh content, she connected the paper with Sam’s Tomadachi strip. The comic became a beloved feature of the paper, and a cultural touchstone for the Japanese-American community.

Dee’s determination is also evident in her work with the Japanese Community and Cultural Center of Washington (JCCCW), established in 2003. In 1990, she led a group advocating for the center, but initially faced resistance from the Japanese School Board. After 13 years of perseverance, Dee built relationships with her opposition and became a key figure in founding the JCCCW, which now houses the Japanese School, a store, and a community center.

Dee is also deeply committed to preserving Nikkei (Japanese emigrant) stories. Her Omoide project, tied to the JCCCW, is a collection of short stories capturing the experiences of the Japanese-American community. Now in its seventh edition, Omoide encourages readers to learn from these stories and apply their lessons to their own lives. Dee believes that confronting difficult truths, including the mistakes rooted in “evil,” is essential to prevent them from being repeated.

Dee’s eyes light up when she talks about Sam, the love of her life. A photo from their 1960 wedding, with Dee gazing lovingly at Sam, captures their enduring love. They were true partners in every sense—marriage, parenting, creativity, and activism. Dee fondly recalls working upstairs in her office while Sam worked in his studio downstairs, with their daughter Kelly growing up in a “newsroom” environment. She misses their conversations about each of Sam’s comic strips, where she was always his greatest support.

Dee is proud of Kelly, who continues her father’s legacy with Seattle Samurai. Kelly’s careful framing of Sam’s work makes it accessible to a wide audience, while “Inu” the dog, Sam’s comic sidekick, adds humor throughout the book.

“Someday I’d really love to tell the story of the love affair of Sam and Dee,” beams Dee. Someday we will.