One day in 1947, when I was seven years old, my mother and I were walking along a dry creek bed on our family ranch near Carey, Idaho, where we had gathered for a reunion, when she suddenly became animated and cried out. Thinking she might have seen a rattlesnake, I ran to her side, but a broad smile on her face quickly appeared.

“Guess what I found,” she said holding in her hand a beautiful, sharply pointed arrowhead. I had never seen a genuine Indian arrowhead, which she explained, had been made hundreds of years before the area had been touched by European American civilization. My young imagination conjured up images of Indians living on our ranch hunting herds of bison, which she affirmed had indeed been the case. In the early 1920’s, small groups of Shoshone occasionally camped in the area, where as a child mother recalled witnessing the birth of an Indian baby in a tent.

I was hooked. From that moment, I began to develop a passionate interest in all things relating to Native American history. Returning home to Idaho Falls, after the reunion, my little hands were sweating from holding the arrowhead so tightly. It quickly had become my most prized possession. I became captivated by the beauty of ancient flaked projectile points, thousands of which are still scattered across Idaho landscapes, many dating back 10,000 years and made from multi-colored gem stones for which Idaho is famous.

My parents fed my passions for Indian lore, taking me to most of the major museums in Idaho and neighboring states. In 1950, our family visited the Little Big Horn battle site located near Harding, Montana, and walked across the huge Sioux encampment area, reading every historical marker and picking up books and souvenirs in the visitor center. Sioux and Cheyenne survivors of the battle with Custer’s Seventh Cavalry were still living at that time.

In the days before television, we sat by the radio with bowls of popcorn listening to a program called “The Idaho Story,” where I first heard the heroic story of Chief Joseph and the Nez Perce fight for freedom in1877. Forced from their ancestral lands in the Wallowa Valley of Oregon, some 750 tribal members led the United States army on a 1300 mile chase, crossing northern Idaho, winning major battles along the way, until they were forced to surrender in the Bear Paw Mountains of Montana, less than 50 miles from the Canadian Border.

Since no copy machines existed in 1950, obtaining a desperately desired photo of Chief Joseph was no small task for a ten year old boy, so I cut his portrait from a library book to hang in my room. I like to think the quilt ensuing from that theft has been assuaged to some degree by my contributions to libraries!

When I was 12, Jess Croft, a local sheep rancher and church leader, obtained permission from Shoshone-Bannock tribal leaders for our youth group to view a sun dance on the Fort Hall Reservation. Few events have affected my imagination so profoundly. Male dancers fasted for several days. Blowing whistles made from the wing bones of eagles, symbolizing the breath of life, and wearing regalia that included moccasins and beautifully crafted, multi-colored beaded belts, the men danced toward a tall tree stripped of branches, crowned by a buffalo head, and then away again. I wondered where the dance had originated and for how many centuries the wistful primeval sounds of those eagle bone whistles had echoed across the Snake River Plain.

Around the arena, dancers rested in huts shaded by freshly cut tree branches. In front of the arena, also shaded with branches, a large circle of men sang and beat dance rhythms on a huge drum, while women in long shawls swayed back and forth, singing. The grounds were covered with cattail rushes. I sat on a log, transfixed, when a very old Shoshone man sat down beside me and began to sing and speak in the Shoshone language. His long white hair was braided, leather sinews wrapped around the end of each braid, and he wore a beautifully beaded vest. Our youth leader, Mr. Croft, told us that his name was Benjamin Tyone, he was more than 90 years old, and as a young man had hunted bison in Montana. In that moment, some 70 years ago, as I viewed the image and countenance of that charismatic, historic personality, the past instantly came to life.

Just recently, I noticed a photograph of Tyone in the publication “History of Lemhi County” written by Hope Benedict. He was a Lemhi-Shoshone who had moved with the rest of his tribe from Salmon to Fort Hall in 1907. During the early 1950’s, Idaho Falls artist Helen Aupperle painted several portraits of Tyone, one of which can be viewed in a mural at the Museum of Idaho in Idaho Falls, depicting Tyone on a horse as he approaches a sun dance at Fort Hall.

A few years after my Sundance experience, while attending a Fort Hall festival in 1957, I had the opportunity to meet Willie Gorge, who as a young man knew Buffalo Bill Cody and performed in the “101 Ranch Wild West Show.” I saw him riding a very tall pinto horse, wearing full regalia, including an eagle feather war bonnet, with feathers fluttering in a light breeze against a vivid blue sky.

There has rarely been anything so beautifully created and crafted by the mind and purpose of man as the Plains Indian War Bonnet. The annual Shoshone-Bannock festival held each August at Fort Hall Provides an insightful opportunity to see eagle feather bonnets in various configurations, along with other regalia worn by tribes in attendance from throughout the West.

At one of the festival events, I was delighted to see tribal member, Randy‘L Teton in a native dress made by her grandmother. Randy was chosen to serve as a model for the US Sacajawea dolor, first issued in 2000.

During service as a member of the Idaho House of Representatives, I often came into contact with tribal members. I fondly recall Representative Jeanne Givens, a member of the Coeur d’Alene tribe, who one day appeared on the house floor wearing a stunning full-length white deerskin dress, beautifully fringed and beaded.

Paulette Jordan, also a member of Coeur d’Alene Tribe, was a house member from Plummer, and in 2018 a candidate for Idaho governor. Her office was next to mine in the Capitol Building, making it convenient for her to feed my interest in all things Native American. She told stories and legends about her people, gave me camas bulbs and huckleberries she harvested, and suggested tribal remedies when I got sick, even supplying medicinal roots. Paulette had a striking elegant presence, standing about six feet in height, with keen intelligent eyes and long black shining hair. She and I planned the 2014 Idaho Day observance in the House where she appeared in full Coeur d’Alene regalia.

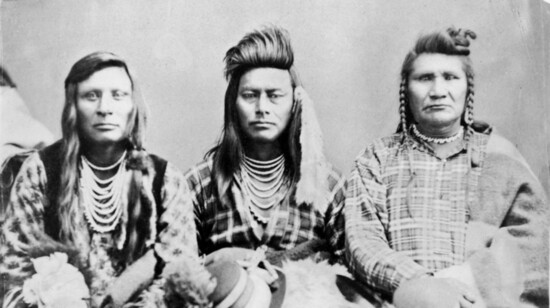

During that celebration, I was astounded to learn that on her mother’s side, Paulette is also Nez Perce and a direct descent of Ollokot, who not only was the brother of Chief Joseph, but the leading warrior in the Nez Perce War. Joseph himself served primarily as camp chief and political leader of the band. Ollokot was described as splendid in appearance, standing more than six feet tall, his hair cut to about seven inches in front and stiffened, so that it stood up like a comb, while very long hair hung down his back. Ollokot inspired the Nez Perce during their horrific struggle, surviving all the fighting until the last battle at the Bear Paw Mountains, where he was killed. His wife had died earlier from wounds suffered at the Big Hole engagement.

On that cold day in October 1877, at Bear Paw, it couldn’t have entered Ollokot’s mind that his beautiful third great granddaughter would one day serve in the Idaho House of Representatives, yet, there she was. The spirit of Ollokot and the tribes of Idaho live on.